Our Changing Watershed: Who are those climate scientists, and why should we believe them?

These folks are the world’s most credible voice on climate change.

By Geoff Ross.

I often hear, or read, sentiments that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) consists of radical scientists trying to scare everyone with overly theoretical forecasts of extreme, but unlikely, impacts of climate change. So who are these IPCC folks, and why should we believe them?

In short, these folks are the world’s most credible voice on climate change; they are more likely underestimating the impacts we face, while advising us on what we must do to preserve a world fit for human survival.

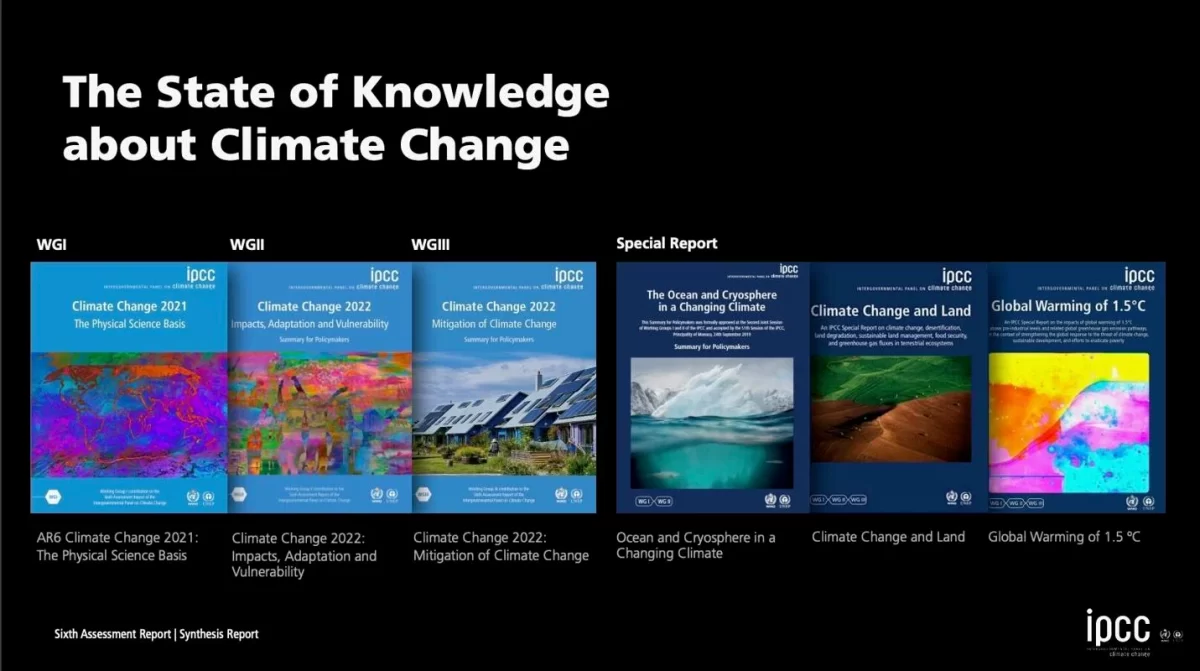

The IPCC was formed by the United Nations (UN) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988 to assess the science related to climate change. It has 195 member countries. It does not conduct its own research, but critically reviews research being done around the world to determine the status of scientific knowledge on climate change. Every five to seven years it prepares an assessment report.

The sixth IPCC Assessment Report (March 2023) was written by a team of 721 authors and review editors from 90 countries. These included a diverse mix of scientific, technical and socio-economic expertise, different regions, developed and developing countries, men and women, and those with industry and not-for-profit backgrounds.

To suggest that such a diverse group could be manipulated to produce a report that is misleading the world with overly severe forecasts is, frankly, ridiculous. In reality, two forces push the IPCC reports to conservative estimates of the severity of climate change.

The first is the diversity of the authors and editors; many are not scientists, and many come from countries that derive substantial economic benefits from the extraction, processing, export and consumption of fossil fuels. IPCC rules and procedures ensure that the views of such individuals are respected. The balance inherent in such a diverse group ensures that the science is absolutely beyond question and protects against overstating the impacts of climate change.

The second is that the scientific method, by its nature, seeks to determine what we know with high confidence. In the realm of climate change, this results in assessments which say, in effect, that “we know with high confidence that climate change will be at least this severe.” Of course we know that it could be more severe, but we are not able to say so with high scientific confidence. Scientists, by their nature, stay within the limits of high scientific confidence and avoid overstatement regarding their conclusions. The result is that the severity of an environmental or health impact has generally been greater than science could initially forecast with high confidence. Examples include the impacts of smoking, phosphorus release to the Great Lakes, mercury releases to rivers, acid rain, ozone depletion and health effects of smog. If we examine the six IPCC assessment reports we see that each successive report predicts more severe impacts and does so with higher confidence. The common factor here is the cautious approach — the avoidance of overstatement, inherent in the scientific method.

It thus becomes important to look beyond what IPCC forecasts with high confidence, and prepare for the more severe outcomes that are forecast with lower levels of confidence. We are now experiencing these — as ice loss at both poles, severe storms, floods, droughts and forest fires beyond what we would have expected based on the high confidence forecasts from past reports.

In summary, the IPCC is the opposite of radical scientists overstating risks. The risks we face are likely more severe and closer in time than forecast by IPCC. We would do well to adopt this perspective when reading the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report and formulating policy. The full report will be a daunting read for most. The “IPCC Climate Change Synthesis Report — Summary for policymakers,” at 42 pages, should be a more manageable read.

We should all read it, note what it says and act on its findings.

This article is one of Muskoka Watershed Council’s summer 2023 series on “Our Changing Watershed” in The Muskokan newspaper. This week’s article was contributed by Geoff Ross, a retired professional engineer and past chair of the Muskoka Watershed Council. He holds a Master’s degree in human physiology and endocrinology. Series editor is Dr. Neil Hutchinson, a retired aquatic scientist, Bracebridge resident and Director, Muskoka Watershed Council.