Monthly Archives: August 2020

Creating climate-resilient communities in Muskoka

By Carley Rennie.

Our world is changing in many ways and the old ways of doing things are no longer sufficient. Such times, although challenging, can bring new opportunities for businesses, municipalities, communities and individuals willing to embrace them. MSE 2021 — the Muskoka Summit on the Environment will explore innovative solutions to build resilience and rise to the challenges of a changing climate.

There is no denying that our climate is changing. The composition of our atmosphere has changed due to increasing amounts of greenhouse gases emitted via various human activities. Consequently, more heat is trapped, and the earth’s temperature is rising. The effects of climate change are experienced differently across the globe, from raging wildfires, heat emergencies, ocean acidification, dying coral reefs, melting permafrost, flooding, and much more. No matter the size or situation of a community there are bound to be impacts, some of which are already being experienced. Thus, it is important that these changes be acknowledged and addressed when planning for the future in order to have a habitable, healthy earth. This is not one problem requiring one solution, but a range of problems that requires a range of solutions developed through a holistic approach involving diverse stakeholders all working toward resiliency.

So, what does climate resiliency mean? Climate resiliency is the ability to plan, respond, and recover from the impacts of climate change. This can look different depending on the nature of an area. For example, a low-lying coastal region should strive to be resilient to rising sea levels. Identifying the climate-related risks of an area are important to determine the best ways to mitigate and rebound from the effects of climate change. Building resiliency into a city can be streamed through various avenues, including natural systems, built infrastructure, transportation, technology, and agriculture. Doing this should lead to sustainable decision-making that strategically guides policy and investment.

There are many emerging innovative solutions to creating climate resiliency for both rural and urban communities. Looking specifically within the scope of Muskoka, there are plenty of concepts, models, and strategies that can be applied across our landscape. For Muskoka, a region situated on the Canadian Shield with a high variance of seasonal populations and expansive lakes and forests, we must consider all these characteristics when implementing climate-resilient solutions. An Integrated Water Management (IMW) white paper has been created by the Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC). This document recommends an approach that includes all aspects of the watershed respecting socio-economic and ecosystem health as well as supporting collaborative solutions specific to Muskoka. Download your copy at https://www.muskokawatershed.org/wp-content/uploads/IWMP-WhitePaper-Jan2020.pdf. Climate-resilient communities are not only healthier for the environment and human beings, but more economical as well.

Understanding how we can add resiliency to Muskoka through our forests, adapting our infrastructure and landscape, our behaviours, and economy are all topics of discussion at the 2021 Muskoka Summit on the Environment. Bringing these perspectives and this information to Muskoka will help mobilize stakeholders to shift toward a resilient future. Now is the time to be proactive rather than reactive to protect the quality of our air, water, land, people, and economy.

While implementing change can seem intimidating, not taking action is a much scarier prospect. Luckily a societal shift in thinking and acting has started; there are certainly people, organizations, and jurisdictions that we can look to for inspiration and guidance in these times. We look forward to discussing the urgency to change and how resiliency is possible in communities such as Muskoka at the upcoming 2021 Muskoka Summit on the Environment: Creating Climate-Resilient Communities. For more information on the summit, see www.muskokasummit.org.

Carley Rennie is a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council and served as a watershed health intern

2021 Muskoka Summit on the Environment looks at climate resiliency

By Carley Rennie.

Our world is changing in many ways and the old ways of doing things are no longer sufficient. Such times, although challenging, can bring new opportunities for businesses, municipalities, communities and individuals willing to embrace them. MSE 2021, the Muskoka Summit on the Environment, will explore innovative solutions to build resilience and rise to the challenges of a changing climate.

There is no denying that our climate is changing. The composition of our atmosphere has changed due to increasing amounts of greenhouse gases emitted via various human activities. Consequently, more heat is trapped, and the earth’s temperature is rising. The effects of climate change are experienced differently across the globe, from raging wildfires, heat emergencies, ocean acidification, dying coral reefs, melting permafrost, flooding, and much more. No matter the size or situation of a community, there are bound to be impacts, some of which are already being experienced. Thus, it is important that these changes be acknowledged and addressed when planning for the future in order to have a habitable, healthy earth. This is not one problem requiring one solution, but a range of problems that requires a range of solutions developed through a holistic approach involving diverse stakeholders all working toward resiliency.

So, what does climate resiliency mean? Climate resiliency is the ability to plan, respond, and recover from the impacts of climate change. This can look different depending on the nature of an area. For example, a low-lying coastal region should strive to be resilient to rising sea levels. Identifying the climate-related risks of an area are important to determine the best ways to mitigate and rebound from the effects of climate change. Building resiliency into a city can be streamed through various avenues, including natural systems, built infrastructure, transportation, technology, and agriculture. Doing this should lead to sustainable decision-making that strategically guides policy and investment.

There are many emerging innovative solutions to creating climate resiliency for both rural and urban communities. Looking specifically within the scope of Muskoka, there are plenty of concepts, models, and strategies that can be applied across our landscape. For Muskoka, a region situated on the Canadian Shield with a high variance of seasonal populations and expansive lakes and forests, we must consider all these characteristics when implementing climate resilient solutions. An Integrated Water Management white paper has been created by the Muskoka Watershed Council. This document recommends an approach that includes all aspects of the watershed, respecting socio-economic and ecosystem health as well as supporting collaborative solutions specific to Muskoka. Download your copy at muskokawatershed.org. Climate resilient communities are not only healthier for the environment and human beings, but more economical as well.

Understanding how we can add resiliency to Muskoka through our forests, adapting our infrastructure and landscape, our behaviours, and economy are all topics of discussion at the 2021 Muskoka Summit on the Environment. Bringing these perspectives and this information to Muskoka will help mobilize stakeholders to shift toward a resilient future. Now is the time to be proactive rather than reactive to protect the quality of our air, water, land, people, and economy.

While implementing change can seem intimidating, not taking action is a much scarier prospect. Luckily a societal shift in thinking and acting has started; there are certainly people, organizations, and jurisdictions that we can look to for inspiration and guidance in these times. We look forward to discussing the urgency to change and how resiliency is possible in communities such as Muskoka at the upcoming 2021 Muskoka Summit on the Environment on Creating Climate-Resilient Communities. For more information on the summit, see www.muskokasummit.org.

Carley Rennie is a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council and served as a watershed health intern

Flooding and the elephant in our Muskoka watershed

We still have a lot more to learn about this elephant that we call severe flooding

by Caroline Konarzewski.

Who wants another flood? Not me!

We hold our breath every time a spring storm with heavy rain is predicted here in Muskoka. Will our cottages and homes be safe? Will the roads to our places be washed out? Why don’t they just use the existing dams to better hold back all that water, so it doesn’t cause us so much grief?

There is a problem with that, though. Perceiving the solution to be only controlling the dams is a little like a blindfolded person feeling an elephant’s tail and deciding that an elephant is small and skinny like a snake. It turns out there is a lot more to the beast than dealing only with that tail!

Often, when you think of a “watershed” you think “water in the rivers and lakes.” That water is just the elephant’s tail. The watershed is everything that the rain and melt water touches and moves over, under, around and through before it collects in the lakes and rivers.

The rain that falls in Muskoka’s forests first hits the trees and then all the shrubs and other growing things. The roots of those trees and other plants suck up some of that rainwater. Evapotranspiration, the evaporation of water from the soil and transpiration (think sweating through their leaves) from trees sends much of the water back into the atmosphere.

Along the way this water sometimes encounters wetland areas that slam the brakes on the water flow. The densely packed growth in these wetlands slows the water down and greedily sucks up a lot of it.

Water that has not been absorbed or slowed down has travelled a long way before it eventually reaches the rivers and lakes. Now that is a huge elephant!

There was a time when Muskoka’s forests and wetlands extended all the way to the shores of our waterways. When we built our homes, cottages and other structures along the shores of our waterways, we removed some of the forest and filled in some of those wetlands and replaced them with hard surfaces and shallow rooted grasses. We have removed those natural elements along the shoreline that help reduce the amount of water entering our waterways.

But in thinking only of the shorelines we are like the blindfolded person touching the elephant’s leg. There is more to that elephant than just its leg, we must look further.

Muskoka is a beautiful part of the world and we want to live here. But we have removed forests and filled in wetlands to build our towns, hard surfaces such as roads, driveways, parking lots, patios, and roofs of buildings. Water collects and picks up speed on these hard surfaces, washing out roads and damaging property. We need to look at ways to correct these problems and make changes for the future.

We still have a lot more to learn about this elephant that we call severe flooding. We must stop ignoring to the enormity of the problem and seek new ways of preventing future disasters.

To that end the Province of Ontario has formed the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group to research the problem and make recommendations to the Province for the future.

An Integrated Water Management (IMW) white paper has been drawn up by the Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC). This document recommends an approach to flood control that includes all aspects of the watershed respecting socio-economic and ecosystem health as well as supporting collaborative solutions specific to Muskoka. Download your copy here: www.muskokawatershed.org/wp-content/uploads/IWMP-WhitePaper-Jan2020.pdf.

We can develop a better understanding of that elephant called flooding. We can learn the best possible ways to live here safely and sustainably, protecting and enhancing the Muskoka paradise we love.

Caroline Konarzewski is a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council.

Saving Skinks!

By Jenn LeMesurier.

The Common Five-lined Skink is listed as a Species at Risk in Ontario, and Muskoka provides habitat to this unique species. Specifically, Five-lined Skinks are found in rock barren environments at the southern edge of Muskoka.

The Common Five-lined Skink is the only lizard native to Ontario and is not often seen due to their quick nature and ability to camouflage. Juveniles and some adults can be readily identified by five cream coloured stripes that extend down the length of their green-black bodies. The species becomes more uniformly bronze with age, though hatchlings and juveniles have bright blue tails. They can grow up to 21 cm in length and, while similar in body shape to salamanders, they have scales and claws which sets them apart.

Skinks in Muskoka are typically found in forest openings, specifically large rocky outcrops, seeking shelter under rocks or tree stumps. Females typically lay between 8-10 eggs in the early summer in a nest under cover (e.g. rotting log). They will leave their nest to bask in the sun, and then return use their bodies to warm their eggs which hatch in the late summer. The hatchlings will be about 3 cm in length.

On cool summer mornings, it’s possible to find Skinks basking in the sun, but most often they are found hiding under cover. They typically hunt in the leaf litter and can even climb trees to escape predators!

The really neat adaptation that Five-lined Skinks have is that their bright blue tail can break off if grabbed by a predator. When the tail breaks it will thrash about for a few seconds which distracts the predator for just long enough that the Skink can escape. Although a new tail will grow back with time, the Skink will have lost much of the fat reserves on which it relies to survive hibernation in the winter.

Five-lined Skinks are listed as a species of Special Concern in Ontario, which means they live in the wild, but could become threatened or endangered. The biggest threats to Skinks in Ontario are the loss and disturbance of habitat. Development and population increase in cottage country has a big impact on species at risk. The removal of cover objects has been observed specifically in the Southern Shield population as rocks are moved in high traffic natural areas and woody debris is moved for firewood. Removal of these objects during nesting season is particularly negative. Illegal collecting for pets, traffic mortality and increased predation all pose significant threats to Five-lined Skinks in Ontario.

So…what can you do?

Protect rock barren habitat for species at risk by keeping development out of these sensitive areas. Maintaining cover objects like rocks and logs that Skinks utilize for refuge is one of the simplest things we can do. When you’re spending time outdoors, remember that we need to respect the need for wildlife to have space in nature. Please don’t build inukshuks along hiking trails, keep your pets on a leash, and maintain natural habitat areas around your own property. You could work to create habitat for Five-lined Skinks on your own property by using coverboards or leaving brush piles and be sure not to disturb known nesting sites.

If you have interest in recording your wildlife sightings, use the iNaturalist app to take photos and notes on the species you come across while out exploring – including Five-lined Skinks! The data collected using this application is used by citizen scientists and environmental professionals alike.

If you’re lucky enough to capture a photo of a Five-lined Skink, be sure to share the sighting. After all, education and awareness for this species is important in helping them thrive!

Jenn LeMesurier is an Ecologist at RiverStone Environmental Solutions Inc. and is a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council.

Native Plants & Shoreline Buffers

Natural shorelines have long been recognized as an important component of healthy and productive waterbodies. Unfortunately, it is still all too common to see landowners clear away the “messy” vegetation in their shoreline area and replace it with lawns and retaining walls.

You can still enjoy your waterfront property while preserving water quality and wildlife habitat by limiting your shoreline development to a small area and leaving the remaining 75% or more of your shoreline in its natural state.

It is important to maintain the scenic beauty and natural character of Muskoka’s lakes and rivers, not only for aesthetic reasons, but for practical ones as well.

Shoreline vegetation benefits water quality by reducing the amount of sediment, nutrients, organic matter and pesticides that enter our rivers and lakes.

There is no better way to prevent soil erosion that to leave your shoreline in its natural state. Plant roots anchor the soil, preventing it from being washed away by currents, waves and rain. This preserves fish spawning beds, which can become destroyed by sediment accumulation due to erosion.

Overhanging branches from trees and shrubs shade the waters to prevent overheating and provide cover for small fish and other aquatic organisms. Debris such as logs and boulders also provide cover for many species, spawning areas for fish, and will serve to reduce the impact of waves on your shoreline.

There are several ways to go about protecting or restoring your shoreline.

- Preservation – a natural shoreline is retained and access to the lake is designed in such a way as to avoid shoreline damage.

- Naturalization – degraded shorelines are left alone to return to their natural state.

- Enhancement – native species are planted and non-native species are removed.

- Restoration – cleared areas are planted with native species.

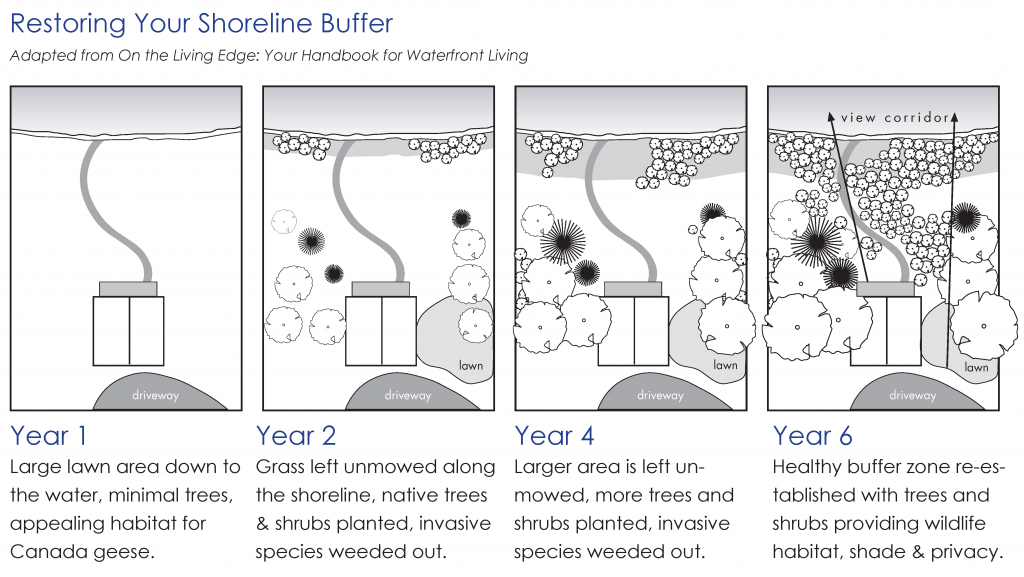

The simplest way to get your altered shoreline back on the right track is through naturalization. Simply mark out an area reaching at least 10 feet back from your shoreline and stop mowing it. Native grasses, shrubs and trees will colonize the area.

The process is an interesting one, with wildflowers and grasses moving in the first year, and trees and shrubs following a year or two later. Non-desirable species can be selectively cut or hand pulled. You can gradually increase the naturalized area each year.

Many native plant species are extremely attractive. You can create an aesthetically pleasing property while providing food and habitat for wildlife, preventing erosion, and maintaining water quality. Take the time to enjoy the view, instead of mowing the lawn.