Monthly Archives: February 2021

Texas Freeze and Muskoka Flooding: What We Can Learn From Recent Events Down South

By Peter F Sale.

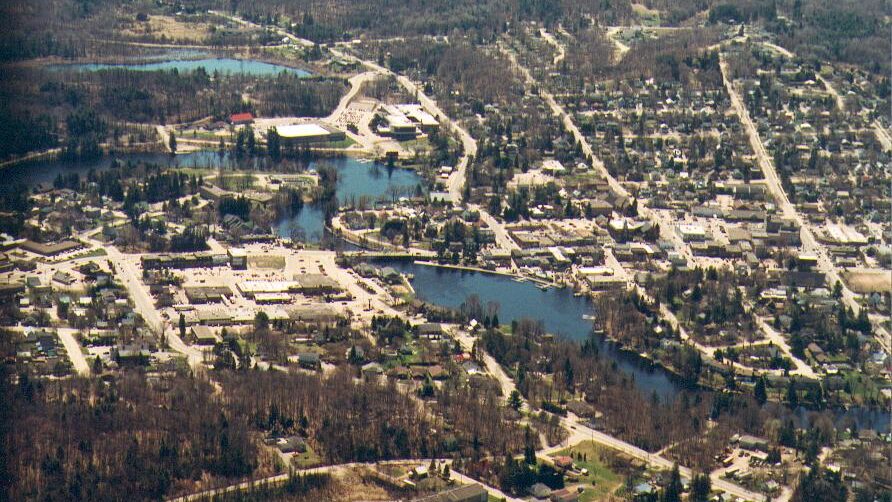

Muskoka has a worsening flood problem: conditions often conspire to produce damaging spring floods, such as those in 2019 and 2013. Our changing climate is increasing this flood risk and there is an expectation in our community that “the government” will take steps to “fix” these risks to our properties and our lives.

Texas has just discovered it has a problem with sudden cold weather. Climate change has now warmed the Arctic sufficiently to cause the polar vortex to become more erratic; the resulting sudden cold snaps are now more prevalent and severe. The cold snap this February has caused widespread hardship, property damage and loss of life because of failures across a power grid that was built without adequate protections for effects of cold weather.

Across the state, inadequately winterized power stations (gas, coal and nuclear) and a few wind turbines failed to deliver power as designed. This coincided with very high demand on electricity supplies given that many Texan homes are heated by electricity. The result? Severe cold inside houses, frozen water pipes, failures at water treatment plants, and flooding of homes once the cold snap eased and ruptured pipes began to leak.

Why did this happen? Because Texan governments, wishing to minimize regulations on industry and keep taxes and utility costs low, did not require the developers of power plants, electricity grids or water treatment plants to install systems that would protect against the one-in-a-hundred-year cold snaps that “never” occur. Such protective systems are routinely installed in jurisdictions further north.

And what has this to do with Muskoka and flooding? Our governments can ignore the likely effects of climate change on flood risk, or take minimal steps, seeking consultants’ reports or hastily building something, anything, that “might” help, and can be done before the next election. Or they can admit we are now in a changeable world in which flood risk could worsen substantially, a world in which “seat-of-the-pants” solutions will not be up to the task. They can implement integrated watershed management (IWM).

Water moves through our environment in complex ways. Half of the rain and snow that falls here never flows to Georgian Bay because it returns to the atmosphere through evaporation and transpiration in our forests. Part of the remainder takes long circuitous paths through wetlands and groundwater, reaching rivers years after it fell as rain or snow. If we are to maximize our ability to tame our rivers and keep our lakes “full” through the summer season, we need to harness the natural infrastructure and find ways to work with Nature rather than try to impose our will on it.

We can implement IWM by first building a detailed understanding of how water moves across the Muskoka River Watershed. Working as partners, the 13 municipalities, the province, First Nations, the power operators, and other economic and societal stakeholders within our watershed, could then use this hydrological understanding to determine

- the flood risks likely to increase,

- the alternative ways to address those risks, and

- the consequences across the watershed and over time of each possible approach.

In this way, IWM leads to the best possible solutions to coming problems, rather than “guessed-at fixes” for past problems.

As well as guiding our flood risk management, IWM can, and should, be used to guide the other aspects of environmental management and land use planning across our watershed. IWM, properly implemented, is perhaps, the only way we can satisfactorily manage flooding and other unexpected consequences of climate change in our community. Yes, it’s more complicated, takes a bit longer and is less obvious than constructing a “honking big” dam, but over the long term will be far more cost-effective and also a much more effective way to manage our incredible, but fragile, Muskoka landscape.

Peter Sale is a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council. This is one of a series of articles from the Muskoka Watershed Council concerning the implementation of Integrated Watershed Management across Muskoka.

Current planning is not doing enough to protect the Muskoka River Watershed

Nor is this planning helping the economy in our changing environment.

By Kevin Trimble.

This article is part of a series to show how Integrated Watershed Management (IWM) is the key to a sustainable future and a climate-resilient economy.

Before we can discuss IWM, we need to understand what’s not working with the status quo. The Muskoka River Watershed is under at least three major kinds of pressure, including climate change, flooding and land use. This article focusses on land use, which refers to the ways in which humans settle on, change, manage, and use the landscape and its natural features.

The Muskoka River Watershed is rich in natural infrastructure in the form of extensive areas under natural vegetation and numerous lakes and waterways. These natural features are vital to our economy and the quality of our lives (https://www.muskokaregion.com/opinion-story/10017241-the-importance-of-natural-infrastructure-in-muskoka/). Effective management will utilize, sustain and grow that natural infrastructure while allowing the development required to house our population and sustain our economy. Natural infrastructure performs many ecological processes or services, such as the natural regulation of water flow through the watershed. 50% of annual precipitation goes back to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration from forests.

Viewing the entire watershed is the best way to understand how our land use decisions affect natural infrastructure. Many of the ecosystem elements and processes that create and maintain natural infrastructure can be understood and measured at that scale.

The challenge is that the watershed is divided up into thirteen separate municipalities that make local land use decisions. Land use is also governed by four upper tier municipalities (Districts) as well as provincial and federal agencies.

The Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) provides direction and frameworks for municipal planning. The PPS calls for municipalities to use the watershed scale for “integrated and long-term planning” and for assessing cumulative effects of land development. However, provincial policy is interpreted differently, or filtered out, as it makes its way through various layers of government to our thirteen local municipalities.

Each municipality is doing its best to protect its important local environmental assets while making decisions that benefit its constituents. In one corner of the watershed a natural feature such as a forested swamp might seem common, expendable and valued mostly for development land. But to a municipality in another part of the watershed, that same feature might be critical for flood mitigation, water quality, carbon sequestration, biodiversity or habitat. There is no strategy to prioritize and link large tracts of habitat across all the municipalities in the watershed. The recent report by the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group stated that decisions being made to meet a local need don’t necessarily consider the overarching importance of sustaining the inter-dependent watershed economy and environment.

Municipalities are currently governing land use without sufficient tools to even assess watershed goals, much less take steps to achieve them. So instead of coordinated progress toward protecting our greatest economic asset, the watershed ecosystem, we’re gradually making things worse (including flooding and climate change). The solution to this governance challenge is not to restructure municipalities or gut our existing system. Decisions on land use changes are already put through local and district processes to confirm site specifics, zoning and land use designations. Integrated Watershed Management won’t add a new layer of bureaucracy and rules; it will allow local municipalities to function autonomously but with better environmental tools that consider the whole watershed. This is the way to sustain natural infrastructure across the entire Muskoka River Watershed and still meet our socio-economic needs.

We will explore the “how’s” in upcoming articles in the IWM series.

Kevin Trimble is Past Chair of the Muskoka Watershed Council. He is a consultant living near Port Carling.